From a Low and Quiet Sea, adapted for the stage from Donal Ryan’s acclaimed, Booker Prize-nominated novel.

Four souls. Each searching for something they have lost. Each trying to make sense of the road they have chosen. For Farouk, family is all. He has protected his wife and daughter from the war. If they stay, they will lose their freedom. If they flee, they will lose all they have known of home, for a faraway land across the merciless sea. Lampy is distracted. He’s with Eleanor, but she’s not Chloe. His granddad’s sniping jokes are getting on his wick. And on top of all that, he has a bus to drive; those old folks from the home can’t wait all day. For John, the game was always the lifeblood coursing through his veins. Manipulating people for enrichment, for enjoyment, for spite. But it was never enough. The lifeblood is slowing down, will God listen? Florence’s son is acting differently which forces her to look for answers, but she is afraid of the truth that lies within herself.

The mother, the refugee, the penitent, the dreamer. Four characters, four lost souls, searching for a version of home.

Adapted by Donal Ryan, the cast, and Andrew Flynn. Directed by Andrew Flynn.

Reviews

The Guardian, 18 July 2022

Author Donal Ryan has a gift for eliciting sympathy even for his characters’ misdeeds. In a new stage adaptation of his Costa-shortlisted novel, the first speaker we are introduced to, John (Lorcan Cranitch), is seeking forgiveness for a life of meanness, cruelty – and worse. It is a lot to ask. For this co-production between Decadent Theatre Company and Galway Arts Centre, the script was developed by Ryan, along with director Andrew Flynn and the impressive cast of four, and retains the lyricism of the novel.

Author Donal Ryan has a gift for eliciting sympathy even for his characters’ misdeeds. In a new stage adaptation of his Costa-shortlisted novel, the first speaker we are introduced to, John (Lorcan Cranitch), is seeking forgiveness for a life of meanness, cruelty – and worse. It is a lot to ask. For this co-production between Decadent Theatre Company and Galway Arts Centre, the script was developed by Ryan, along with director Andrew Flynn and the impressive cast of four, and retains the lyricism of the novel.

In a series of separate monologues unfolding over two hours, four characters in a small Irish town try to make their peace with painful pasts. For Syrian doctor Farouk (Aosaf Afzal), memories of his wife and daughter who drowned on their treacherous journey in a migrant boat cause him to blame himself. Meanwhile John, a property owner and shady financial dealer, recalls past bullying and the young woman he tried to coerce through obsessive love. Cranitch brings a bitter note of self-loathing to his confessions, spitting out the term he had used to describe his role as a blackmailing middleman: “a lobbyist”.

Florence (Maeve Fitzgerald) anxiously watches over her son, Lampy (Darragh O’Toole), as if trying to compensate for the absent father he never knew; Lampy nurses a broken heart for his first love while wondering how to escape from the town and his bus-driving job at a care home. For all his frustrations, his bravado and comic running commentary on his elderly passengers lighten the otherwise sombre tone.

On a stripped wooden stage with designer Ger Sweeney’s abstract backdrop and Ciaran Bagnall’s lighting evoking the sea and wide sky, there is little to distract from the performances. These are subtle and often gripping, as the successive monologues build to create character studies, some sketchier than others. Yet the relationship between them does not reveal itself until the end, when all four characters are finally on stage together, in a striking tableau. Rather than an “aha” moment, this feels a little rushed, so that instead of highlighting the rich threads of connection between disparate lives, the lingering impression is more of isolation.

The Irish Times, July 12, 2022

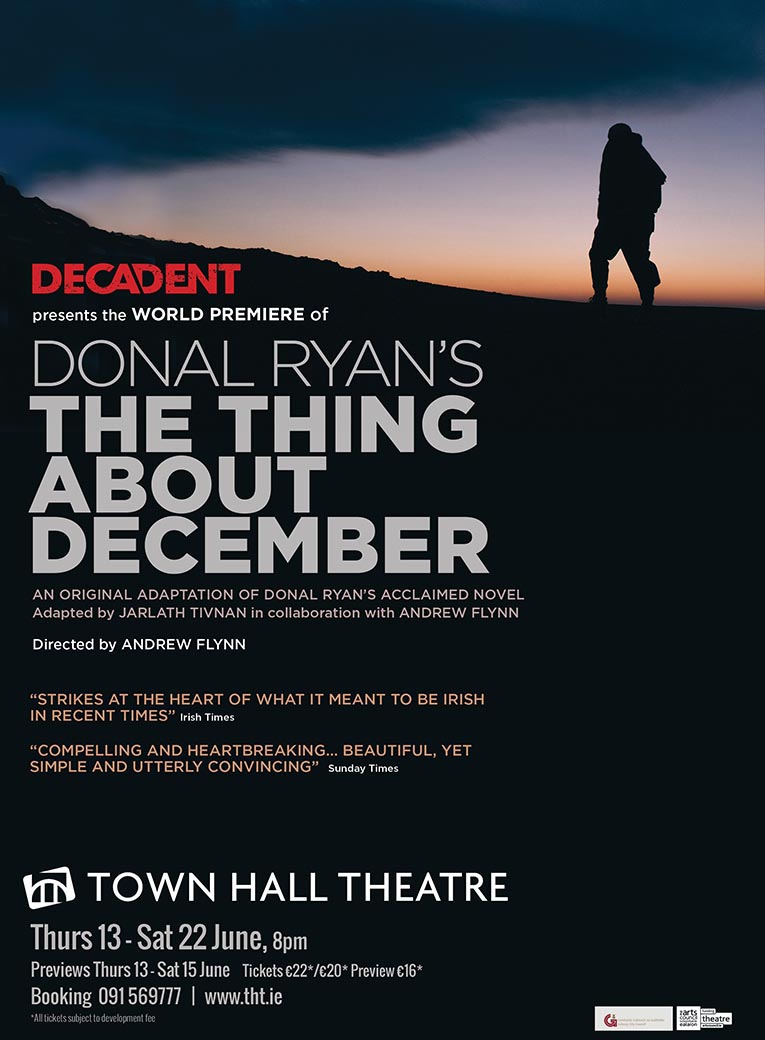

On paper, Donal Ryan’s novels seem perfectly suited to theatrical adaptation. The urgent first-person narratives of Ryan’s The Spinning Heart and The Thing About December have already been successfully staged in Ireland, the interwoven voices providing audiences with intimate engagements with his characters, whose fates are aligned in surprising and unpredictable ways.

On paper, Donal Ryan’s novels seem perfectly suited to theatrical adaptation. The urgent first-person narratives of Ryan’s The Spinning Heart and The Thing About December have already been successfully staged in Ireland, the interwoven voices providing audiences with intimate engagements with his characters, whose fates are aligned in surprising and unpredictable ways.

Decadent Theatre were responsible for the adaptation of The Thing About December in 2019, and director Andrew Flynn leads the staging of From a Low and Quiet Sea, adapted from the 2018 novel by Ryan in collaboration with Flynn and the actors.

The plot revolves around four personal narratives, each presented in monologue form by single actors on a sparely-designed stage. John (Lorcan Cranitch) is a man at the end of his life, reckoning with his own sins, unsure who he should seek forgiveness from. Florence (Maeve Fitzgerald) carries the past with her too; the secret of her son’s father and his shocking acts of “love”. Farouk (Aosaf Afzal) is fleeing war with his young family, whom he accidentally sacrifices in pursuit of their freedom. Lampy (Darragh O’Toole) is mourning the loss of his first love, trying to figure out what the future holds for him.

Lampy is the best drawn of these characters, a familiar Ryan type, a small-town jack-the-lad with complex family relationships. Here, Lampy’s voice is distinguished from the poetic monotone of the other characters too. With idiosyncratic vocal tics and a unique self-deprecating tone, O’Toole brings a distinct energy to his confessionals too. The quiet, relatable realism of his character arc distinguishes Lampy’s tale from the melodramatic reach of the story’s denouement, in which the characters’ lives come suddenly together in the final moments.

The play is simply staged on bleached wood floorboards against an abstract grey backdrop designed by Ger Sweeney. When lit by Ciaran Bagnall, the oversized canvas becomes the sea, the sky, the sunset and a boat on a raging stormy sea. The actors come and go as they tell their stories, and this is the production’s key mistake, producing laboured transitions between the unfolding narratives that slows the momentum down. This changes towards the end of the second act, as the characters’ relationships start to become clear. Indeed, the final tableau, where Cranitch is frozen in a pose of penitent genuflection and the other actors join him on stage, offers a belated moment of deep theatrical resonance for the audience, where the staging finally matches the emotional heft of Ryan’s language.

The Irish Independent, July 12, 2022

It might seem like an unimaginative programming choice to stage two premieres with the same underlying theme during a major arts festival. But Galway International Arts Festival (GIAF) knew what it was doing: the isolation and personal torment of the bereaved refugee can never be far from any of our minds in these times. Both The Last Return (Druid at the Mick Lally Theatre) and From a Low and Quiet Sea (Decadent Theatre Company and Galway Arts Centre at Nun’s Island Theatre) confront the theme, but could not be more different from each other…

It might seem like an unimaginative programming choice to stage two premieres with the same underlying theme during a major arts festival. But Galway International Arts Festival (GIAF) knew what it was doing: the isolation and personal torment of the bereaved refugee can never be far from any of our minds in these times. Both The Last Return (Druid at the Mick Lally Theatre) and From a Low and Quiet Sea (Decadent Theatre Company and Galway Arts Centre at Nun’s Island Theatre) confront the theme, but could not be more different from each other…

There are no laughs in the adaptation for the stage of Donal Ryan’s novel From a Low and Quiet Sea. It is relentlessly and deeply depressing, leaving one moving from horror to pity in throat-choking shifts of mood throughout. Ryan and director Andrew Flynn have chosen (in cooperation with the cast) to put the piece on stage in a series of monologues that seem to touch barely tangentially; until the final terrible moments when four tragic lives collide in unspeakable realisation of their separate and joint desolation.

It is not very often that four demanding and intense roles come together with absolute perfection, but they do in this production. Not a moment, a nuance, a gesture is less than perfect throughout, as each of the characters in turn drag the heart from your body.

Lorcan Cranitch is John, the elderly citizen who was once the grand panjandrum of his town, with his dodgy accountancy business, his property portfolio, his Jaguar… and his double life that will entrap young Florence (Maeve Fitzgerald), leaving her to recover as best she may, only finally to face an utter destruction that even in her worst moments she could never have envisaged.

And there’s young Lampy (Darragh O’Toole), once cocky, but now having to content himself with a dead-end job driving the local care bus; once he might have gone to university; once lovely Chloe might have loved him. No more.

And beyond them, Farouk (Aosaf Afzal), his tragedy far across the sea, where as a young doctor he was enticed and threatened, to entrust himself and his family to false promises of a new life. He saw terrible things: he watched as a flogged woman was thrown from a truck, a notice ‘adulteress’ pinned to her body. As a male, he was not allowed to help her. Otherwise, it was hinted, his wife might be raped, his little daughter sold. It would be his punishment for failing to observe fully the brutal code that was the order of the day. Now he prays only that his wife and daughter did reach a shore somewhere and are not at the bottom of the sea which so nearly claimed him when he succumbed to the promises and threats.

Lighting is by Ciaran Bagnall, with sound and music by Carl Kennedy and the backdrop design by Ger Sweeney.

This play will haunt you.